Origins of Prêt-à-Porter or Ready-to-Wear is an urban legend. Some would attribute it to Yves Saint Laurent line and boutique Rive Gauche or Elsa Schiaparelli 1935 and her Place Vandome boutique.

“A new Schiap era came into being with the place Vendome. The year 1935 was such a busy one for Schiap that she wonders how she got through. To start with there was the birth of the Boutique. The Schiap Boutique, the very first of its kind, has since been copied not only by all the great Paris couturiers but the idea has spread all over the world, especially in Italy. It became instantaneously famous because of the formula of ‘ready to be taken away immediately’. There were useful and amusing gadgets afire with youth. there were evening sweaters, skirts, blouses, and accessories previously scorned by the haute couture. — Shiaparelli, Elsa. Shocking Life: The Autobiography of Elsa Schiaparelli (p. 65)

Scenario Framing

The scholarly sources, however, reference the military and the War of 1812 in which production advances and the difficulty of executing men tailoring, military uniforms were mass-produced.

In parallel, country workers in the nineteenth century France had to abandon tailor-made suits as they could no longer sustain the tradition and their wives were incompetent to tailor domestically— a situation that eventually led to a simplified version of what they previously wore making it possible for manufacturers to mass-produce them.

Source: The 7th NY Dragoons, visible above were at the battle. The most likely uniform of the 680 NY militia is the uniform second from the left — War of 1812 Wargaming Blog

A similar story went for women’s apparel. The practice was up and running before 1900 where workers in towns bought and wore ready-made interpretation of the traditional regional costumes. In parallel, city employees and petit bourgeoisie shopped at department stores where clothes were more imaginative than what their country peers could find, while prices remained affordable.

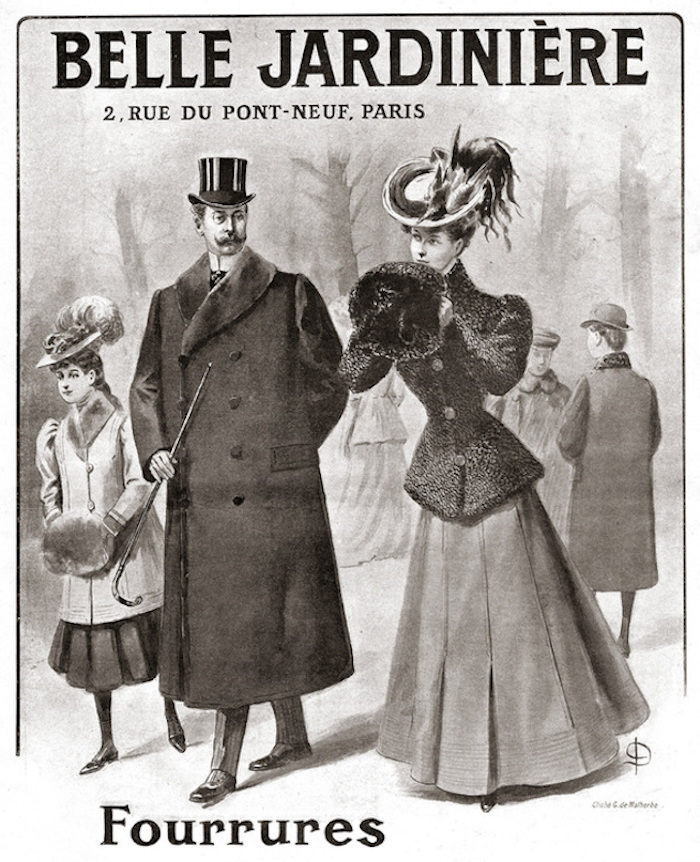

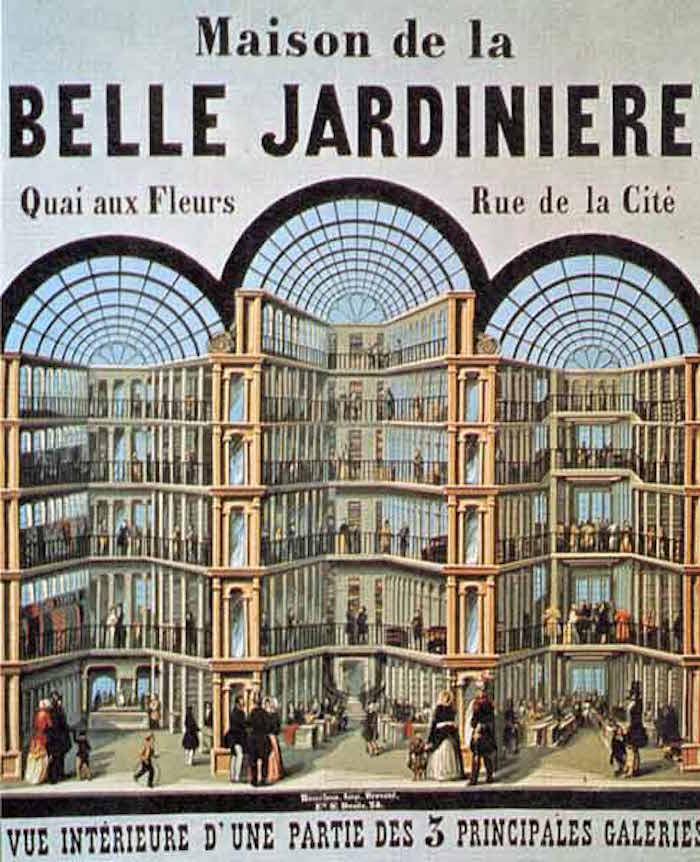

According to the Histoires de la mode by Didier Grumbach in 1867, the oldest Parisian department store at the time, La Belle Jardinière, was also the biggest prêt-à-porter manufacturer employing over 1,500 external workers and 50 cutters in his workshop.

Les Grands Magasins Parisiens

Les Grands Magasins Parisiens

Three decades later and moving to another continent, the United States struggled with the financial crisis which waved goodbye to the great Jazz age paving the way to the machine age that mainstreamed life in its totality.

During those years, American Fashion houses formed an active apparel industry with particular support to local talents given by both the retail and the Hollywood Film industry. The advances in technology also meant that people were able to travel for leisure, leading to an increased interest in Sportswear for both men and women— a category championed by and closely linked to American Designers up until today.

The real tangible growth of American Fashion and British for that matter arose during World War Two. As occupied Paris drove most French Couturiers to close their houses, American retailers and consumers alike abandoned Paris Fashion News and consequently their merchandise. The war also forced women back to the workforce giving way to trousers, shorter silhouettes, and innovation due to lack and restriction of materials. The change crystallized in the 1942 with ‘utility’ design – standard material produced in large quantities along with severe ‘austerity’ rules controlling optimum conditions in which clothes are made with the least materials possible vanishing pleats and extra pockets and shortening skirts and dresses hemlines.

Source: Summers, Julie. “Did WW2 Introduce Designer Fashion to Our High Streets?” BBC IWonder, BBC, www.bbc.co.uk/guides/zpjckqt.

You have to give it to the French though that even with all the hardship they experienced during the German occupation, they found a way to express their fashion as a matter of national pride.

In her book The Japanese Revolution in Paris fashion, Yuniya Kawamura quotes a person from the French fashion industry at the time:

“We wore large hats to raise our spirits. Felt gave out, so we made them out of chiffon. Chiffon was no more. All right, take the straw. No more straw? Very well, braided paper…. Hats have been a sort of contest between French imagination and German regulation…. We wouldn’t look shabby and worn out; after all, we were Parisiennes.”

By 1947 retailers and designers in Paris, London, and the United States were free again to resume the game. Under the helm of Lucien Lelong, The Chambre Syndical de la Couture Parisienne created the Théâtre de La Mode (Theatre of Fashion)— a touring made of small-scale wire mannequins about a third of the human scale, wearing the latest work of the best in class French designs.

Jeanne Lafaurie. Approx. 29” tall. Maryhill Museum of Art, Goldendale, Washington.

Théâtre De La Mode Mannequin with Draped Dress and Accessories, www.maryhillmuseum.org.

Paris and New York led the fashion industry during the period of post world war II, yet the two cities had very different approaches and philosophies regarding style and the making of it: French Designers continued with their exaggerated obsession with tailored elegance championed by Christian Dior and Cristobal Balenciaga. American fashion houses, on the other hand, had their hearts set on casual sporty designs.

The fraction between the two capitals created an ideal climate for Italian fashion to build stamina. Which leads us to the birth of the Italian fashion story that officially started in 1951 Florence: another tale of taste, innovation, and an intricate symbol of what it means to be Italian.

… To be continued

fin. . .