In sharp contrast to that of its present status, pre-twentieth century bag played an elaborated role in which it answered the practical needs of the wearer and a restricted stylistic code linked to predefined situational context.

One recurrent theme nonetheless, that stretches through the ages, is the role of the bag as a social differentiators. It symbolises a multitude of social codes and communicates social identities by conveying occupations, domestic environments and possessions, use of leisure time, modes of travelling and so on.

Species for genus (hypernymy) – the use of a member of a class (hyponym) for the class (superordinate) which includes it (e.g. a ‘mother’ for ‘motherhood’, ‘bread’ for ‘food’, ‘Hoover’ for ‘vacuum-cleaner’) — Chandler, Daniel. Semiotics: The Basics (p. 121)

A glance at fashion history confirms that just like all other fashion categories, the bag has ancient symbolic roots expressing the needs and tastes of both the wearer and its time.

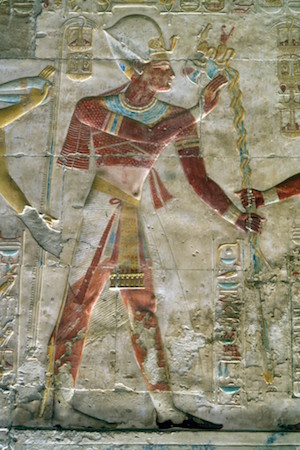

For instance, in 3150 BC Ancient Egypt wealthy men held their precious items in leather or cloth bag worn around their waist. The functional need nevertheless almost vanished around the sixteenth century as men and women kept their valuables in added pockets to suits and hidden ones in big dresses.

Art of Counting,Seti I wearing a red fabric shirt, armbands, double shebiu collar, multiple apron, and looped sash

Art of Counting, www.artofcounting.com Seti I wearing a looped sash while grasping a rekhyt bird

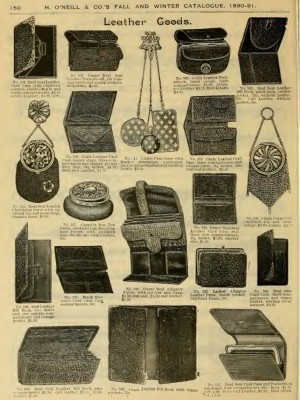

Luckily though, these dresses evolved through time, and their sizes shrank for a more slender silhouette mirroring the mood of the French revolution. This new practical volume demolished pockets and gave way again to bags. The item became a fashionable one particularly in the Victorian era where it was designed in many different shapes and fabrics that matched the wearer outfit.

“Victorian Accessories: Gloves, Bag, Hat, Brooch, and Parasol.” VintageDancer.com, Sept. 2016

“Collections.” The Museum of London Collections | Search Thousands of Collections Online.

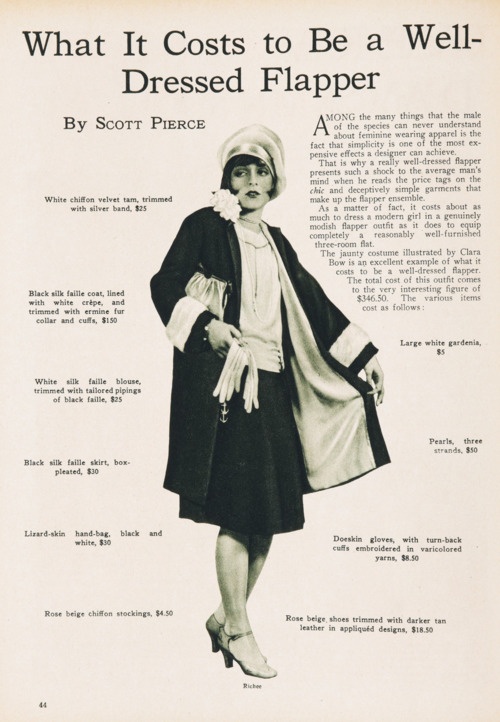

Dolores Monet describes the times that came after WWI as “A kind of cynicism that came in the aftermath of World War I and the devastating flu pandemic of 1918 created a youth culture that glorified fast living, dancing, and the exciting sounds of syncopated jazz described by the writer F. Scott Fitzgerald as the Lost Generation.”

And once again, handbags mirrored that air of cynicism: They were merely bags held in your hand with some lipstick, a small case of powder, a house key, and a few coins according to Debbie and Oscar Sessions founders of the Vintage Dancer. This shift made the handbag the ultimate fashion accessory: for the morning women carried ones made from fabric tooled leather, while in the evening they went for beaded sparkly ones that matched their Jazz dancing outfits.

Source: Rinsema, Kate. “The Cost of Flapper Fashion Done Right.” Holy Kaw!, Sept. 2012

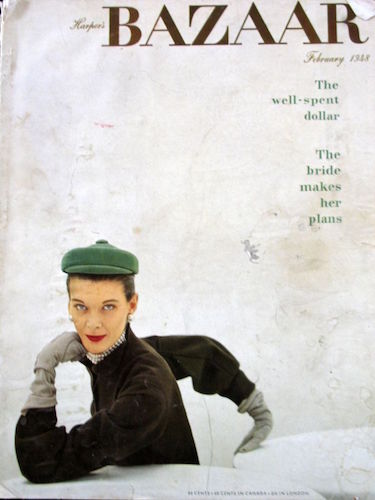

This power of abstraction is behind the success and sometimes survival of many luxury fashion labels. In fact, leather goods constitute a big piece of the global luxury pie. It isn’t a surprise to industry insiders as it is the one fashion item that is sizeless, seasonless and, most importantly, projects “membership of the group.” The bag stamina is tightly linked to the mid-twentieth century regard for fashion. A perception curated mainly by pop culture— Film, photography and the fashion press. At the time, if a person did not belong to the international fashion elite, she would not care about what is happening in the couture industry per se. What mattered was the contemporary idea of what a woman looked like (or is supposed to look like). This information was chiefly and easily retrieved from Glossy magazines such as Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar that both mastered linking fashion to a city and a way of being.

Spencer, Victoria, et al. “Diana Vreeland: An Illustrated Biography Is Like Fashion Porn.”

PreAdored™. “Vintage Harper's Bazaar Magazine February 1948.” PreAdored™, preadored.com

This notion of fashioning the city is epitomised in the collective romantic idea of New York in which it solidated its positioning as the American cultural metropolitan hub through a deliberate promotion evident in literature, music, film, television series and, most evidently, fashion publications. The power that pop culture had, and still enjoys today through different mediums, on the industry can be seen in the numerous case studies of fashion labels launched due to an association with hit series or an Editor-at-Large endorsement.

The most memorable story of all has to be the Carrie Bradshaw’s one taking place, where else, in New York City. One episode after another, Carrie’ narrative is linked to her relationship with the city and how she saved her recurrent identity crisis, misfortunes, and heartbreaks by endorsing a Manolo Blahnik, a Fendi bag, and in one extreme case a couture dress by Vivienne Westwood. Some observers would even link the birth of the IT bag to that moment in which Carrie’s Fendi Baguette is recognised by a street robber making her the most recognised designer bag at the time by a mass scale. Even Wikipedia somehow links the definition of an IT Bag at the same time

“A colloquial term from the fashion industry used in the 1990s and 2000s to describe a brand or type of high-priced designer handbag by makers such as Chanel, Hermès or Fendi that becomes a popular best-seller.”

And while the position of luxury fashion bags is tightly linked to European luxury fashion houses, the first documented one was not. It was around 1892 in Plainville, Massachusetts that an American brand, Whiting and Davis, designed and produced a very elaborate metal mesh bag combining Art Deco enamel with a colourful pattern printed through silk screening known today as The Dresden mesh.

“What's So Special About Whiting & Davis Metal Mesh Handbags?” The Spruce, www.thespruce.com

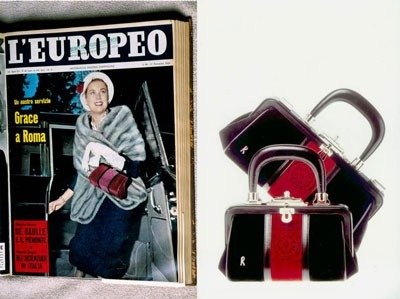

The first recognised IT bag, however, unsurprisingly, is Italian made. Created by Giuliana Coen di Camerino who is credited for making the first identifiable status-bag around 1945. The Camerino handbag was an avant-garde one that used soft leather bags closed with a double fold. The fame it enjoyed was due primarily to design in opposition to the severe dominant trend at the time that accessories design shared: A bag, must match the colour of the shoes. Her most iconic design though was Bagonghi— The name was inspired by a little clown from the designer childhood and was made with colourful velvet and a peculiar shape.

Source: “Le Mie It-Bags: La Bagonghi Di Roberta Di Camerino.” Legally Chic, 2013.

Fast forward few decades and the Chanel quilt bag with the double Cs of the logo place at its front. Karl Lagerfeld interpretation of the original 1955 Coco Chanel 2.55 glit and quilt bag paved the way for all other major fashion players to revamp their classics as identifiers of status. From that moment on, fashion consumers and professionals alike needed no lecturing about what followed. From Louis Vuitton graffiti bag designed by Marc Jacobs, the Paddington by Chloé, the Motorcycle by Balenciaga, the Lanvin Olga Sac, the Givenchy Bettina, the Alexa by Mulberry, Celine luggage tote, and even the latest entry courtesy to Mansur Gavriel Bucket Bag the fashion luxury bag is here to stay.

What concerns us here is the host of non-verbal codes embodied in the bag and facilitating social differentiation. The role of fashion since its inception stays the same: communicating our identities, how we see the world, and where we want to go.

“We learn to read the world in terms of the codes and conventions which are dominant within the specific socio-cultural contexts and roles within which we are socialized. In the process of adopting a way of seeing, we also adopt an ‘identity’. The most important constancy in our understanding of reality is our sense of who we are as an individual. Our sense of self as a constancy is a social construction which is overdetermined by a host of interacting codes within our culture… Learning these codes involves adopting the values, assumptions and worldviews which are built into them without normally being aware of their intervention in the construction of reality.” — Daniel Chandler. Semiotics: The Basics

fin. . .